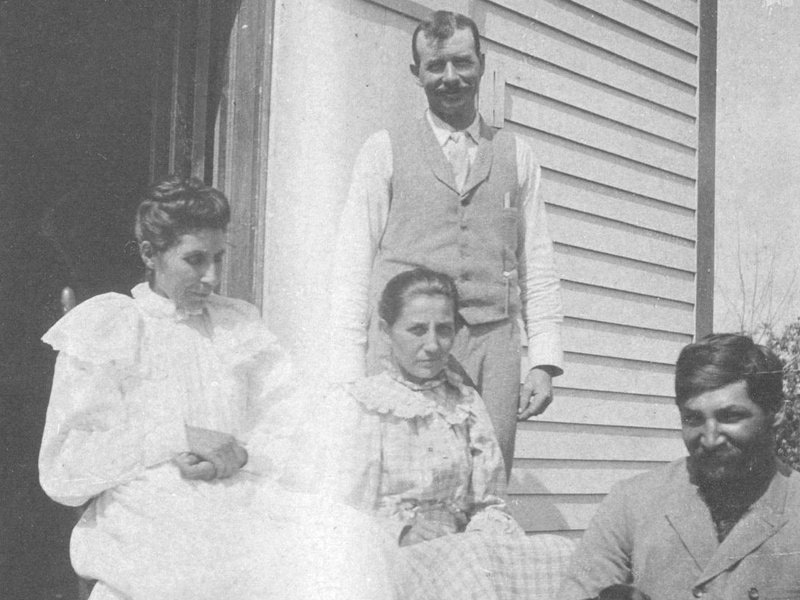

| Found this fascinating article on the Smithsonian website. The picture shows Susan, far left, with her husband (seated with puppy) at their Bancroft, Nebraska, home. (Courtesy of the Hampton University Archives) This is a wonderful story. |

With few rights as a woman and as an Indian, the pioneering doctor provided valuable health care and resources to her Omaha community.

When 21-year-old Susan La Flesche first stepped off the train in Philadelphia in early October 1886, nearly 1,300 miles from her Missouri River homeland, she’d already far surpassed the country’s wildest expectations for a member of the so-called “vanishing race.”

Born during the Omaha’s summer buffalo hunt in June 1865 in the northeast corner of the remote Nebraska Territory, La Flesche graduated second in her class from the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, now Hampton University. She was fluent in English and her native tongue, could speak French and Otoe, too. She quoted scripture and Shakespeare, spent her free time learning to paint and play the piano. She was driven by her father’s warning to his young daughters: “Do you always want to be simply called those Indians or do you want to go to school and be somebody in the world?”

The wind-whipped plains of her homeland behind her once again, she arrived in Philadelphia exhausted from the journey, months of financial worry, logistical concerns, and of course, by the looming shadow of the mountain now before her: medical school. Within days, she would attend her first classes at the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, a world apart from the powwows, buffalo hunts and tipis of her childhood.

Standing at the vanguard of medical education, the WMCP was the first medical school in the country established for women. If she graduated, La Flesche would become the country’s first Native American doctor. But first, she would need to break into a scientific community heavily skewed by sexist Victorian ideals, through a zeitgeist determined to undercut the ambitions of the minority.

“We who are educated have to be pioneers of Indian civilization,” she told the East Coast crowd during her Hampton graduation speech. “The white people have reached a high standard of civilization, but how many years has it taken them? We are only beginning; so do not try to put us down, but help us to climb higher. Give us a chance.”

Three years later, La Flesche became a doctor. She graduated as valedictorian of her class and could suture wounds, deliver babies and treat tuberculosis. But as a woman, she could not vote—and as an Indian, she could not call herself a citizen under American law.

**********

In 1837, following a trip to Washington on the government’s dime, Chief Big Elk returned to the Omaha people with a warning. “There is a coming flood which will soon reach us, and I advise you to prepare for it,” he told them. In the bustling streets of the nation’s capital, he’d seen the future of civilization, a universe at odds with the Omaha’s traditional ways. To survive, Big Elk said, they must adapt. Before his death in 1853, he chose a man with a similar vision to succeed him as chief of the Omaha Tribe - a man of French and Indian descent named Joseph La Flesche, Susan’s father.

“Decade after decade, [Joseph] La Flesche struggled to keep threading an elusive bicultural needle, one that he believed would ensure the success of his children, the survival of his people,” writes Joe Starita, whose biography of La Flesche, A Warrior of the People, was released last year.

Joseph’s bold push for assimilation - “It is either civilization or extermination,” he often said - wasn’t readily adopted by the whole tribe.

Soon the Omaha splintered between the “Young Men’s Party,” open to the incorporation of white customs, and the “Chief’s Party,” a group loyal to traditional medicine men who wouldn’t budge. When the Young Men’s Party started building log cabins rather than teepees, laying out roads and farming individual parcels, the conservatives nicknamed the north side of the reservation “The Village of the Make-Believe White Men.” It was here, in a log cabin shared by her three older sisters, that Susan grew up learning to walk a tightrope between her heritage and her future.

“These were choices made to venture into the new world that confronted Omahas,” says John Wunder, professor emeritus of history and journalism at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. “The La Flesche family was adept at learning and adopting languages, religions, and cultures. They never forgot their Omaha culture; they, we might say, enriched it with greater knowledge of their new neighbors.”

It was here, in the Village of the Make-Believe White Men, that La Flesche first met a Harvard anthropologist named Alice Cunningham Fletcher, a women’s rights advocate who would shepherd her to the East and up the long, often prejudiced ladder of formal education.

And it was here, in the Village of the Make-Believe White Men, that a young Susan La Flesche, just 8 years old, stayed at the bedside of an elderly woman in agonizing pain, waiting for the white agency doctor to arrive.

Four times, a messenger was sent. Four times, the doctor said he’d be there soon. Not long before sunrise, the woman died. The doctor never came. The episode would haunt La Flesche for years to come, but it would steel her, too. “It was only an Indian,” she would later recall, “and it [did] not matter.”

**********

None of the challenges of her education could fully prepare La Flesche for what she encountered upon her return to the reservation as physician for the Omaha Agency, which was operated by the Office of Indian Affairs. Soon after she opened the doors to her new office in the government boarding school, the tribe began to file in. Many of them were sick with tuberculosis or cholera, others simply looking for a clean place to rest. She became their doctor, but in many ways their lawyer, accountant, priest and political liaison. So many of the sick insisted on Dr. Susan, as they called her, that her white counterpart suddenly quit, making her the only physician on a reservation stretching nearly 1,350 square miles.

She dreamed of one day building a hospital for her tribe. But for now, she made house calls on foot, walking miles through wind and snow, on horseback and later in her buggy, traveling for hours to reach a single patient. But even after risking her own life to reach a distant patient, she would often encounter Omahas who rejected her diagnosis and questioned everything she’d learned in a school so far away.

Over the next quarter-century, La Flesche fought a daily battle with the ills of her people. She led temperance campaigns on the reservation, remembering a childhood when white whiskey peddlers didn’t loiter around the reservation, clothing wasn’t pawned and land wasn’t sold for more drink. Eventually she did marry and have children. But the whiskey followed her home. Despite her tireless efforts to wean her people away from alcohol, her own husband slipped in, eventually dying from tuberculosis amplified by his habit.

But she kept fighting. She opened a private practice in nearby Bancroft, Nebraska, treating whites and Indians alike. She persuaded the Office of Indian Affairs to ban liquor sales in towns formed within the reservation boundaries. She advocated proper hygiene and the use of screen doors to keep out disease carrying flies, waged unpopular campaigns against communal drinking cups and the mescal used in new religious ceremonies. And before she died in September 1915, she solicited enough donations to build the hospital of her dreams in the reservation town of Walthill, Nebraska, the first modern hospital in Thurston County.

**********

And yet, unlike so many male chiefs and warriors, Susan La Flesche was virtually unknown beyond the Omaha Reservation until earlier this year, when she became the subject of Starita’s book and a PBS documentary titled “Medicine Woman.”

“Why did they say we were a vanishing race? Why did they say we were the forgotten people? I don’t know,” says Wehnona Stabler, a member of the Omaha and CEO of the Carl T. Curtis Health Education Center in Macy, Nebraska. “Growing up, my father used to say to all of us kids, ‘If you see somebody doing something, you know you can do it, too.’ I saw what Susan was able to do, and it encouraged me when I thought I was tired of all this, or I didn’t want to be in school, or I missed my family.”

The Omaha tribe still faces numerous health care challenges on the reservation. In recent years, charges of tribal corruption and poor patient care by the federal Indian Health Service has dogged the Winnebago Hospital, which today serves both the Omaha and Winnebago tribes. The hospital of La Flesche’s dreams closed in the 1940s - it’s now a small museum - marooning Walthill residents halfway between the 13-bed hospital seven miles north, and the Carl T. Curtis clinic nine miles east, to say nothing of those living even further west on a reservation where transportation is hardly a given. Alcoholism still plagues the tribe, alongside amphetamines, suicide and more.

But more access to health care is on the way, Stabler says, and La Flesche “would be very proud of what we’re doing right now.” Last summer, the Omaha Tribe broke ground on both an $8.3 million expansion of the Carl T. Curtis Health Education Center in Macy, and a new clinic in Walthill.

“Now people are putting her story out, and that’s what I want. Maybe it’s going to spark another young native woman. You see her do it, you know you can do it, too.""

Yes, truly a wonderful story.

When 21-year-old Susan La Flesche first stepped off the train in Philadelphia in early October 1886, nearly 1,300 miles from her Missouri River homeland, she’d already far surpassed the country’s wildest expectations for a member of the so-called “vanishing race.”

Born during the Omaha’s summer buffalo hunt in June 1865 in the northeast corner of the remote Nebraska Territory, La Flesche graduated second in her class from the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, now Hampton University. She was fluent in English and her native tongue, could speak French and Otoe, too. She quoted scripture and Shakespeare, spent her free time learning to paint and play the piano. She was driven by her father’s warning to his young daughters: “Do you always want to be simply called those Indians or do you want to go to school and be somebody in the world?”

The wind-whipped plains of her homeland behind her once again, she arrived in Philadelphia exhausted from the journey, months of financial worry, logistical concerns, and of course, by the looming shadow of the mountain now before her: medical school. Within days, she would attend her first classes at the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, a world apart from the powwows, buffalo hunts and tipis of her childhood.

Standing at the vanguard of medical education, the WMCP was the first medical school in the country established for women. If she graduated, La Flesche would become the country’s first Native American doctor. But first, she would need to break into a scientific community heavily skewed by sexist Victorian ideals, through a zeitgeist determined to undercut the ambitions of the minority.

“We who are educated have to be pioneers of Indian civilization,” she told the East Coast crowd during her Hampton graduation speech. “The white people have reached a high standard of civilization, but how many years has it taken them? We are only beginning; so do not try to put us down, but help us to climb higher. Give us a chance.”

Three years later, La Flesche became a doctor. She graduated as valedictorian of her class and could suture wounds, deliver babies and treat tuberculosis. But as a woman, she could not vote—and as an Indian, she could not call herself a citizen under American law.

**********

In 1837, following a trip to Washington on the government’s dime, Chief Big Elk returned to the Omaha people with a warning. “There is a coming flood which will soon reach us, and I advise you to prepare for it,” he told them. In the bustling streets of the nation’s capital, he’d seen the future of civilization, a universe at odds with the Omaha’s traditional ways. To survive, Big Elk said, they must adapt. Before his death in 1853, he chose a man with a similar vision to succeed him as chief of the Omaha Tribe - a man of French and Indian descent named Joseph La Flesche, Susan’s father.

“Decade after decade, [Joseph] La Flesche struggled to keep threading an elusive bicultural needle, one that he believed would ensure the success of his children, the survival of his people,” writes Joe Starita, whose biography of La Flesche, A Warrior of the People, was released last year.

Joseph’s bold push for assimilation - “It is either civilization or extermination,” he often said - wasn’t readily adopted by the whole tribe.

Soon the Omaha splintered between the “Young Men’s Party,” open to the incorporation of white customs, and the “Chief’s Party,” a group loyal to traditional medicine men who wouldn’t budge. When the Young Men’s Party started building log cabins rather than teepees, laying out roads and farming individual parcels, the conservatives nicknamed the north side of the reservation “The Village of the Make-Believe White Men.” It was here, in a log cabin shared by her three older sisters, that Susan grew up learning to walk a tightrope between her heritage and her future.

“These were choices made to venture into the new world that confronted Omahas,” says John Wunder, professor emeritus of history and journalism at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. “The La Flesche family was adept at learning and adopting languages, religions, and cultures. They never forgot their Omaha culture; they, we might say, enriched it with greater knowledge of their new neighbors.”

It was here, in the Village of the Make-Believe White Men, that La Flesche first met a Harvard anthropologist named Alice Cunningham Fletcher, a women’s rights advocate who would shepherd her to the East and up the long, often prejudiced ladder of formal education.

And it was here, in the Village of the Make-Believe White Men, that a young Susan La Flesche, just 8 years old, stayed at the bedside of an elderly woman in agonizing pain, waiting for the white agency doctor to arrive.

Four times, a messenger was sent. Four times, the doctor said he’d be there soon. Not long before sunrise, the woman died. The doctor never came. The episode would haunt La Flesche for years to come, but it would steel her, too. “It was only an Indian,” she would later recall, “and it [did] not matter.”

**********

None of the challenges of her education could fully prepare La Flesche for what she encountered upon her return to the reservation as physician for the Omaha Agency, which was operated by the Office of Indian Affairs. Soon after she opened the doors to her new office in the government boarding school, the tribe began to file in. Many of them were sick with tuberculosis or cholera, others simply looking for a clean place to rest. She became their doctor, but in many ways their lawyer, accountant, priest and political liaison. So many of the sick insisted on Dr. Susan, as they called her, that her white counterpart suddenly quit, making her the only physician on a reservation stretching nearly 1,350 square miles.

She dreamed of one day building a hospital for her tribe. But for now, she made house calls on foot, walking miles through wind and snow, on horseback and later in her buggy, traveling for hours to reach a single patient. But even after risking her own life to reach a distant patient, she would often encounter Omahas who rejected her diagnosis and questioned everything she’d learned in a school so far away.

Over the next quarter-century, La Flesche fought a daily battle with the ills of her people. She led temperance campaigns on the reservation, remembering a childhood when white whiskey peddlers didn’t loiter around the reservation, clothing wasn’t pawned and land wasn’t sold for more drink. Eventually she did marry and have children. But the whiskey followed her home. Despite her tireless efforts to wean her people away from alcohol, her own husband slipped in, eventually dying from tuberculosis amplified by his habit.

But she kept fighting. She opened a private practice in nearby Bancroft, Nebraska, treating whites and Indians alike. She persuaded the Office of Indian Affairs to ban liquor sales in towns formed within the reservation boundaries. She advocated proper hygiene and the use of screen doors to keep out disease carrying flies, waged unpopular campaigns against communal drinking cups and the mescal used in new religious ceremonies. And before she died in September 1915, she solicited enough donations to build the hospital of her dreams in the reservation town of Walthill, Nebraska, the first modern hospital in Thurston County.

**********

And yet, unlike so many male chiefs and warriors, Susan La Flesche was virtually unknown beyond the Omaha Reservation until earlier this year, when she became the subject of Starita’s book and a PBS documentary titled “Medicine Woman.”

“Why did they say we were a vanishing race? Why did they say we were the forgotten people? I don’t know,” says Wehnona Stabler, a member of the Omaha and CEO of the Carl T. Curtis Health Education Center in Macy, Nebraska. “Growing up, my father used to say to all of us kids, ‘If you see somebody doing something, you know you can do it, too.’ I saw what Susan was able to do, and it encouraged me when I thought I was tired of all this, or I didn’t want to be in school, or I missed my family.”

The Omaha tribe still faces numerous health care challenges on the reservation. In recent years, charges of tribal corruption and poor patient care by the federal Indian Health Service has dogged the Winnebago Hospital, which today serves both the Omaha and Winnebago tribes. The hospital of La Flesche’s dreams closed in the 1940s - it’s now a small museum - marooning Walthill residents halfway between the 13-bed hospital seven miles north, and the Carl T. Curtis clinic nine miles east, to say nothing of those living even further west on a reservation where transportation is hardly a given. Alcoholism still plagues the tribe, alongside amphetamines, suicide and more.

But more access to health care is on the way, Stabler says, and La Flesche “would be very proud of what we’re doing right now.” Last summer, the Omaha Tribe broke ground on both an $8.3 million expansion of the Carl T. Curtis Health Education Center in Macy, and a new clinic in Walthill.

“Now people are putting her story out, and that’s what I want. Maybe it’s going to spark another young native woman. You see her do it, you know you can do it, too.""

Yes, truly a wonderful story.